It’s going to be Chinese New Year soon, and I will have the pleasure yet again of watching my Instagram feed explode into the annual celebration of Chinese-ness and the not so Chinese display of ootds. While I prepare my body and soul for new year feasting, I see my mother busy with preparations of her own.

First she buys a traditional Chinese calendar (months in advance), because it is less common for shops to give those out for free in contemporary times. She scours the stores for one that includes tiny inscriptions of lucky days and unlucky days.

The planning starts.

The symbolism has been explained to me many times. But this was all superstition, and I was puzzled. Did my mother really believe it would work? My mother notes the lucky days and has to perform a series of tasks on those days.

The tasks include changing out the old, leftover rice for new rice, replacing the shrivelled, yellow garlic leaves on the kitchen counter for new ones and replacing the rice cake (sometimes mouldy). The items take up space on the kitchen counter, and made comprehending them even harder.

When all explanations failed, my mother would say ‘it’s a Cantonese thing, you are Cantonese’.

I am indeed, a subpar Cantonese.

But one thing about Chinese New Year that I have always looked forward to is seeing my very small extended family fit into the living room, speaking dialect. I could understand Cantonese, because from a young age I felt it necessary to get in on the latest family gossip.

There is a certain warmth to be felt when you are surrounded by family, when they are fussing over you in dialect and they smile in understanding when you reply in Chinese.

After missing four years of Chinese New Year from studying abroad, I am looking forward to being present in a room that is bustling with celebration.

Watching my mother rush to complete her chores has always been a big part of the pre-celebration, and even after missing out for four years, I still remember what to do.

Because even though I did not indulge in the superstition, I loved the symbolism.

My Chinese New Year in Manchester circa. year of the chicken

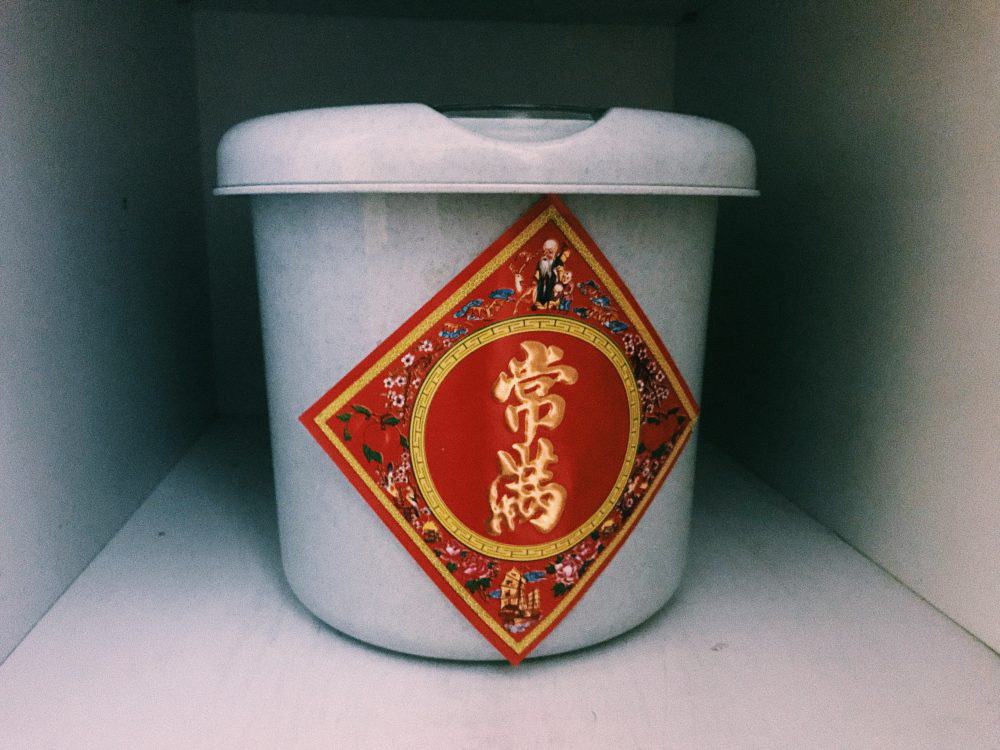

A full jar of rice with a red sticker reading ‘满 (full)’ symbolises just that- abundance. An ancient promise of wealth, success, and good health. Perhaps even more important for families of the past and present with so little to go by, where a full jar of rice meant sustenance.

Garlic leaves for wealth and good financial planning, as garlic shares the same pronunciation as ‘calculation’ in Cantonese. Rice cakes and their promise for a better year.

Long-lasting abundance

Besides the typical new year fare of cookies and mandarin oranges and drinks, there will also be a layered box of food that we prepare religiously every year- the ‘tray of togetherness’. Inside it, there are watermelon seeds for growing families, candied dried fruits, and candy for a sweet life.

Box of candied fruits

There are other things that Cantonese people commonly prepare as well, such as sugar cane for a sweet life (and a sweet treat post feasting), two fishes for extra wealth, cabbage, also for wealth, arrowhead for a growing family, celery for diligence because they share the same pronunciation in Cantonese, and carrots, which share the same pronunciation as gold.

This is on top of the typical things commonly found in a home during Chinese New Year, such as pussy willow, and decorations in red to celebrate the coming of Spring.

I have always felt nervous about losing touch with my roots.

It seems likelier that Chinese New Year traditions and dialects will be diluted with the coming generations. There is something special about gatherings in which everyone speaks a language you are not entirely familiar with, and you are forced to be an observer, forced to listen closely and learn.

Every Chinese New Year, I feel small again, as I am surrounded by tradition and practice pre-dating our time here on this little island. I feel this nervousness even more, now that I am older and the choice of whether to continue the traditions and rituals has fallen on me.

Maybe in many years to come I will purchase a Chinese calendar and my children will watch as I replace the old with the new in symbolic practice.

Because tradition does not have to make sense all the time, most of the time it is superstition, a story passed down from generation to generation.

It makes me feel safe, it roots me in my past and makes a promise for the future, that perhaps even as everything changes around us in today’s society, the warmth of family and reunion will remain.

My children will look at the rice cakes and the garlic leaves yellowing on the counter and they will ask what the significance of all this is. Surely it is just superstition? And when all other explanations fail, I will use the best one-

I am Cantonese.